By Isaac Kofi Agyei & SBM Intelligence

The global cocoa industry faces unprecedented challenges as cocoa supplies tighten and prices surge, impacting chocolate manufacturers and consumers worldwide. Oxfam reports that the chocolate industry saw immense profits at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, with major corporations like Hershey, Lindt, Mondelēz and Nestlé collectively amassing nearly $15 billion in profits from their confectionery divisions.

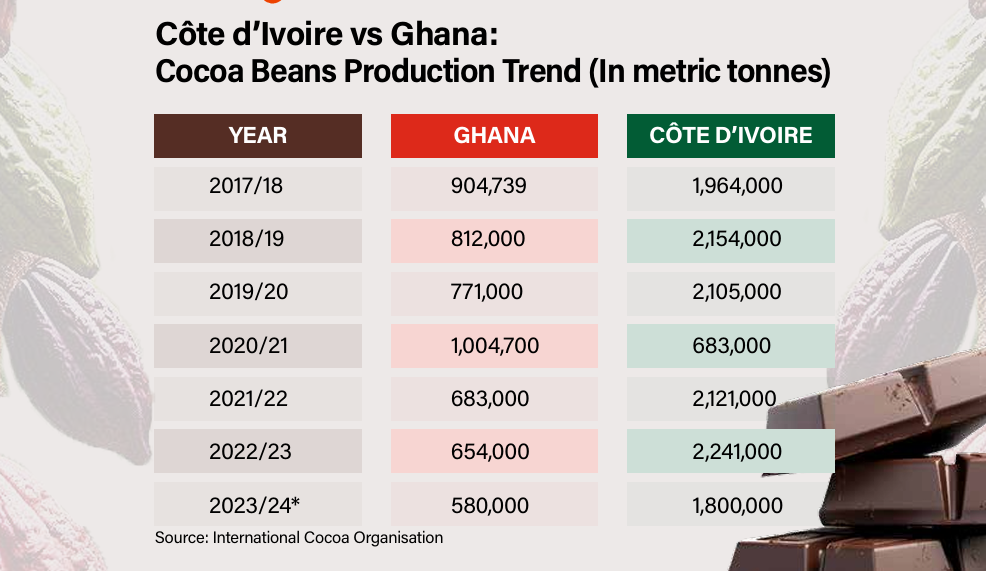

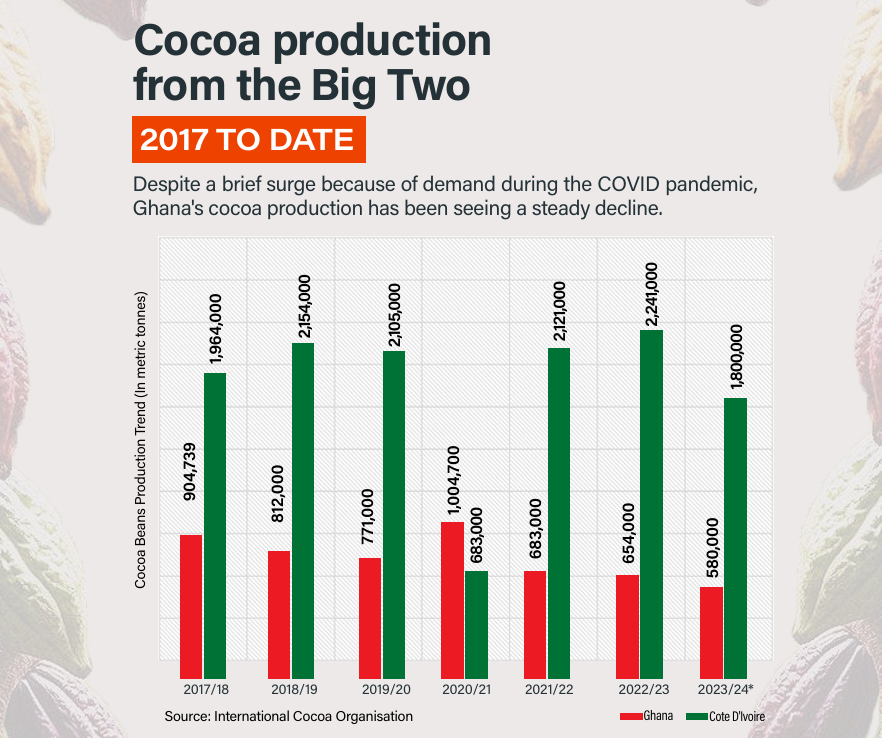

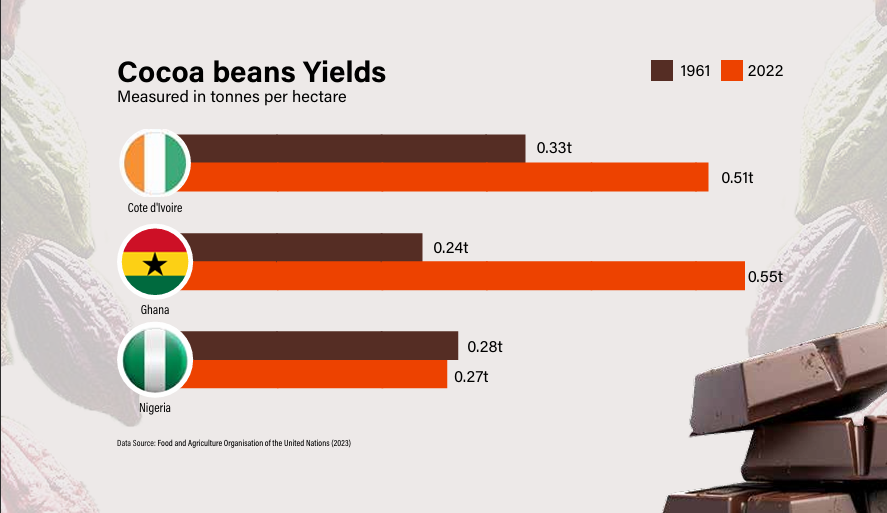

However, this prosperity has been short-lived as cocoa production faces significant setbacks, particularly in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, the world’s largest cocoa producers. Recent data indicates a substantial decline in cocoa bean production projections for the 2023/24 crop season in both Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, attributed to adverse weather conditions and the rapid spread of swollen shoot disease.

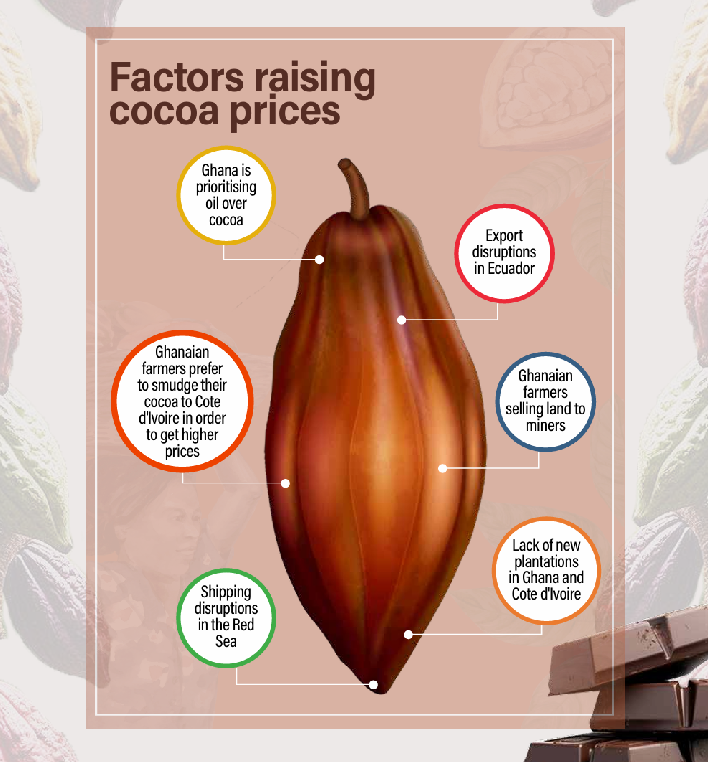

Illegal mining activities and political influences further exacerbate the situation, leading to a severe shortage of cocoa beans. This shortage has caused cocoa prices to skyrocket, impacting retail prices globally and raising concerns about the sustainability of chocolate demand.

Geopolitical events such as increased freight rates and export disruptions have also contributed to the rise in cocoa prices. In response to the crisis, the Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD) and the Côte d’Ivoire Coffee and Cocoa Council (CCC) have authorised measures such as importing cocoa beans and urging cooperatives to sell stocks promptly to prevent hoarding. However, major cocoa processing plants in both countries have either ceased operations or reduced processing due to the inability to afford beans at current prices.

The situation is further complicated by the breakdown of regulated markets, with local dealers paying premiums above regulated prices to secure beans, leading to financial constraints for processors. Additionally, efforts to remain loyal to international customers have raised geopolitical tensions, particularly in Côte d’Ivoire, where anti-French sentiments are spreading.

Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, which supply approximately 60% of the world’s cocoa beans, must carefully navigate this landscape to ensure economic stability. While efforts to aid local processors and restrict global traders have shown some success, more sustainable solutions are needed to address the root causes of the cocoa crisis. One potential solution involves prioritising measures to increase cocoa output and ensuring fair prices for farmers.

A more open market approach could enable Ghanaian cocoa companies to expand regionally and internationally, leveraging their expertise and resources across West Africa. However, addressing these challenges requires political will, cooperation, and investment in research, infrastructure and transportation networks. By adopting a proactive approach and embracing innovation, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire can overcome the current cocoa crisis and build a more resilient cocoa industry.

The lay of the land

The chocolate industry currently faces multifaceted challenges, ranging from fluctuating cocoa supplies to geopolitical tensions and inadequate infrastructure. Various factors converge to threaten the stability and profitability of this crucial sector.

The decline in cocoa production, particularly in key producing countries like Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, not only poses a significant risk to these countries’ economies but also to global cocoa supply chains. This could lead to severe price surges and supply shortages, unlike during the pandemic. In contrast to today’s challenges, an Oxfam report shows that the four largest public chocolate corporations—Hershey, Lindt, Mondelēz and Nestlé—accumulated substantial profits at the start of the pandemic.

Cocoa beans were relatively cheap, and demand for chocolate products rose due to the lockdown. Between 2020 and 2022, these corporations collectively amassed nearly $15 billion in profits from their confectionery divisions, distributing on average more than their total net profits (113%) to shareholders.

Additionally, the combined wealth of the Mars and Ferrero families, who own the two largest private chocolate corporations, has surged by $39 billion since 2020. Now less than three years after this honeymoon period, the same companies are now struggling to buy beans for production due to the shortage that has led to the price hikes.

The International Cocoa Organisation’s projection indicates a significant decline in bean production for Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire in the forthcoming 2023/24 crop season.3 This impending decrease in production poses a substantial threat to the stability of the cocoa industry and its stakeholders, raising concerns about future supply adequacy and pricing dynamics.

This production data represents a significant decrease of 550,000 tonnes, or 24%, compared to the 2022-23 production of 2.3 million tonnes. The International Cocoa Organisation (ICCO) has also expressed concerns about the 2024-25 crops in West Africa, highlighting the potential for a fourth consecutive global deficit in the upcoming season.

Besides adverse weather conditions, the spread of swollen shoot disease has significantly impacted cocoa production in the region. Industry sources say this sharp decline may indicate a fundamental shift from cocoa beans to palm as a result of the incurable viral cocoa tree disease.

“It’s normal for cocoa bean supplies to be limited at this time, known as the ‘last crop’ period, indicating that yields are not as significant as during the main seasons like August or September,” a trader in Accra said.

“However, this current shortage is unusually severe, unlike anything I’ve experienced in my nearly two decades of trading. Ghanaian authorities seem to have deprioritised cocoa since the discovery of oil. “We’ve allowed illegal miners to take over lands, and the distribution of fertilisers has become politicised, with allocation often depending on one’s political affiliation. Personally, I believe that while swollen shoot disease has contributed to this shortage, the activities of illegal miners are making cocoa farming and trading less profitable.

“This has led to more farmers leaving the industry, exacerbating the shortage more than diseases alone. Furthermore, the impact of the disease is not evenly spread across the country; it is concentrated in specific regions and areas.”

Notably, land cannot be replanted for five years after removing infected trees, exacerbating the situation. Previously, farmers would relocate to new forested areas and replant trees, but recent environmental restrictions in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire have prevented this practice.

Data from the US Department of Agriculture indicates that New York cocoa bean futures prices have consistently reached 46-year highs since September; London ICE cocoa futures have also achieved record highs in multiple consecutive sessions. The price surges in cocoa have had a ripple effect, impacting retail prices as well.

Geopolitics intervenes

Recent geopolitical events have also contributed to the rise in cocoa prices. Factors such as increased freight rates resulting from Houthi terrorist attacks in the Red Sea4 and export disruptions in Ecuador,5 the third-largest cocoa exporter, due to drug-related gang violence, have raised cocoa prices.

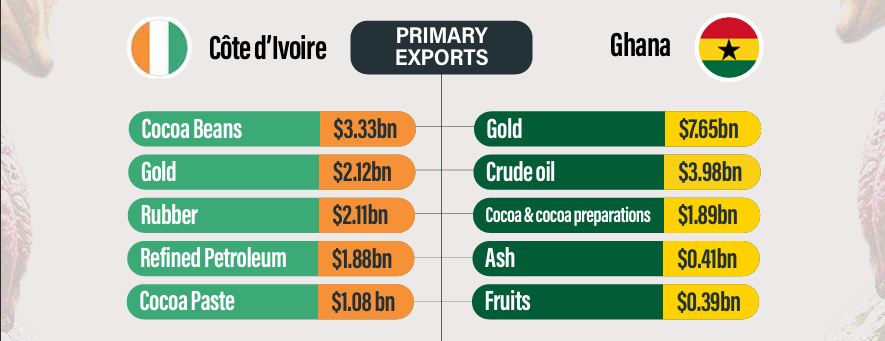

Despite the historically resilient consumer demand for chocolate products, many industry experts are worried that continuous price hikes could eventually destroy demand. In Ghana, while cocoa is slowly declining in its role as one of the top three foreign exchange earners, its crucial contribution to maintaining the stability of the Ghanaian Cedi must not be underestimated.

Ghana’s cocoa industry has faced challenges in maximising its potential. Despite a bold move less than a year ago to increase the price per bag of cocoa beans by 63.5%6 to incentivise farmers and boost yields, domestic and external debt restructuring hindered Ghana’s ability to obtain funds from cocoa-syndicated loans.

Instead of the expected $3 billion, the Ministry of Finance update shows only $800 million was received, leading to delays and disruptions in purchasing beans. Compounding these issues, farmers have sold cocoa farms to illegal miners, further threatening Ghana’s cocoa yield. Farmers assess the potential by evaluating the proximity of their lands to the nearest gold mining site.

“ The decision to sell my farm to galamsey operators was relatively easy compared to say a decade ago when cocoa farmers were treated well,” a farmer in the Ashanti region said. “Despite farming 45 acres of cocoa land, I have been unable to build even a single room all these years due to financial constraints. The value of land with a higher potential for gold can reach GHS 80,000 ($6,000), while those with lower prospects are priced at GHS 20,000 ($1,700).

“As a farmer, I struggle to obtain enough fertilisers for my cocoa farms. It has been two years since I last received seven bags of cocoa fertiliser, while others, with no cocoa farms, seem to effortlessly acquire up to 200 bags. This stark contrast in access to fertilisers, driven by political influences in the cocoa sector, has contributed to my decision to gradually step away from farming.”

The poor condition of roads in cocoa growing communities, known as cocoa roads, has made it cumbersome for farmers to transport harvested cocoa pods from their farms. The bad roads have led to an increase in haulage cost by the Cocoa Board (COCOBOD), thereby increasing the price of cocoa. Despite that, the price is not good enough for farmers who prefer to smuggle their harvested cocoa beans and sell in Côte d’Ivoire at prices higher than the stipulated prices set by COCOBOD. The combination of a substantial decrease in cocoa arrivals, estimated to be over 20% compared to the previous season, and the deteriorating road infrastructure has raised worries about smuggling and hoarding. This situation could potentially disrupt the local cocoa market.

In response to the shortage, the COCOBOD management officially authorised the importation of 3500 metric tonnes of cocoa beans from Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria.7 In Côte d’Ivoire, the Cocoa Council (CCC) has urged cooperatives and buyers to sell their stocks to exporters within 21 days to prevent hoarding,8 exacerbating market instability.

Major cocoa processing plants in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire have either ceased operations or reduced processing due to the inability to afford beans at current prices, prompting chocolate makers to increase prices for consumers globally. Also, local chocolate makers struggle to produce chocolate using raw cocoa, so they rely on processors to turn beans into butter and liquor for chocolate production, but the processors say they cannot afford to buy the beans.

For instance, state-controlled Ivorian bean processor Transcao, one of the country’s nine prominent plants, said it had stopped buying beans because of their price. It said it was still processing from stock but did not say what capacity it was running at. Two industry sources said the plant was almost idle. In Ghana, two sources said more major state and privately run plants could shut down sooner or later.

Usually, the market is heavily regulated: traders and processors purchase beans from local dealers up to a year in advance at pre-agreed prices. Local regulators then set lower farmgate prices that farmers can charge for beans. The breakdown of the regulated market system during shortages has led to local dealers paying farmers premiums above the regulated farmgate prices to secure beans, which they then sell at higher spot prices rather than delivering them at pre-agreed rates. As a result, local processors struggle to obtain the cocoa they pre-ordered, facing financial constraints exacerbated by rising spot prices.

Another contributor to the demand-supply imbalance is the effort of each country to remain loyal to its regular international customers, which can potentially lead to geopolitical tensions, especially in Côte d’Ivoire, where anti-French sentiments are spreading.

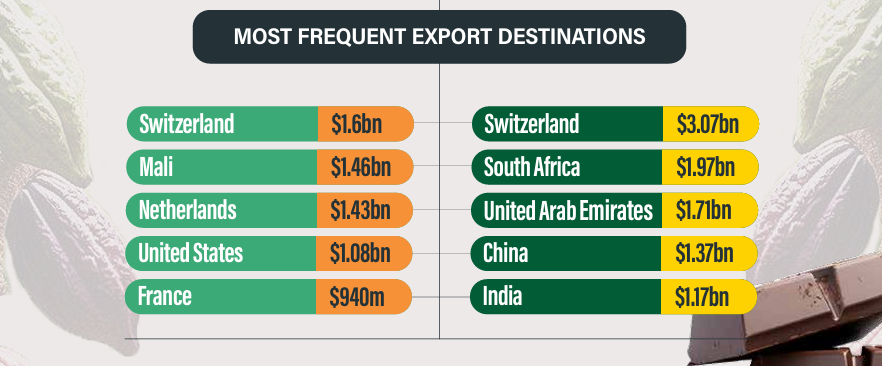

Recent Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) data reveals that Côte d’Ivoire’s primary exports include Cocoa Beans ($3.33 billion), Gold ($2.12 billion), Rubber ($2.11 billion), Refined Petroleum ($1.88 billion) and Cocoa Paste ($1.08 billion). While the country’s most frequent export destinations are Switzerland ($1.6 billion), Mali ($1.46 billion), Netherlands ($1.43 billion), the United States ($1.08 billion) and France ($940 million), France is not among its top five destinations.

This is because while France receives a significant volume of exports from Côte d’Ivoire, other countries like the Netherlands, Belgium and the UK import larger quantities from Côte d’Ivoire, ranking higher in total export value. France is among Ghana’s top five cocoa export destinations, whereas its former colonial ruler, Britain, accounts for less than 3% of total cocoa bean exports.

This is partly due to the Netherlands acting as a middleman, the widespread use of child labour in Ghana’s cocoa industry and the occasional presence of mercury in its direct exports. Interestingly, Ghana and the Ivory Coast do not include their former colonial rulers among their top five cocoa bean export destinations, showing a divergence in geopolitical ties. Issues with child labour pale in comparison with geopolitical needs. In April 2024, the European Union parliament approved rules to ban in the EU the sale, import and export of goods made using forced labour.

This new rule–with China’s alleged child labour practices in Xinjiang in mind– mandates that national authorities in the 27-country bloc or the executive Commission will be able to investigate suspicious goods, supply chains, and manufacturers. Preliminary investigations should be wrapped up within 30 working days. If a product is deemed to have been made using forced labour, it will no longer be possible to sell it in the EU market and shipments will be intercepted at the EU’s borders.

Despite the new legislation, it is likely that the current arrangement between Ghana and Ivory Coast and the EU will remain. Beyond this is another or more pressing issue especially for cocoa farmers in West Africa. Cocoa farmers are facing an impending regulatory burden from the European Union (EU), their largest market.

As of December 30, 2024, the EU will prohibit the importation of commodities such as cocoa, palm oil, rubber, soy, coffee, and wood unless traders can prove that their production did not contribute to deforestation or forest degradation. Given the existing limitations on intensive farming on land already used for cocoa, this policy is likely to exert downward pressure on production for the foreseeable future. There is likely to be lax domestic enforcement and ineffective NGO-led certification mechanisms will be the additional consequences of the EU ban, potentially undermining its intended impact.

Holland is key

Both Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire prioritise selling more than 10% of their cocoa beans to the Netherlands. The Netherlands has long been a prominent destination for a large portion of cocoa beans produced in West Africa. It serves as a central hub for the secondary export of cocoa beans to many key Eurozone countries. According to the OEC data from 2022, the Netherlands imported $1.68 billion worth of cocoa beans, making it the largest cocoa bean importer. The primary recipients of cocoa bean exports from the Netherlands include Germany, France, Italy, Austria and Belgium.

Notably, between 2021 and 2022, the Netherlands experienced substantial growth in cocoa bean exports to France, Belgium and Estonia. For decades, Amsterdam has effectively operated as the largest cocoa intermediary, procuring directly from top producers worldwide, especially in Africa, and distributing to neighbouring European countries.

For the first time in a considerable period, the nearly 200% increase in cocoa bean prices compared to last year could present significant challenges for Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire in deciding which global public chocolate corporations to sell scarce cocoa to.

The Netherlands has traditionally been the primary destination for both countries, ahead of any other Western country. Ghana has diversified its export destinations to include non-Western consumers like Malaysia, which accounts for over 12% of its annual cocoa bean exports. Similarly, Malaysia plays a significant role in Côte d’Ivoire’s export mix, comprising about 11% of its yearly cocoa exports.

Price hikes

While efforts by the Ghanaian and Ivorian authorities to aid local processors with affordable loans and restrictions on global traders have shown some success, the current cocoa shortage has left numerous processing plants unable to afford beans. This situation has resulted in additional price hikes for chocolate products worldwide. In West Africa, cocoa farmers are closely monitoring the spread of various plant diseases, which are causing widespread damage to crops and driving up the cocoa price to unprecedented levels.

In Côte d’Ivoire, concerns are mounting that cocoa farmers may demand an immediate rise in the price per bag following their dissatisfaction last year when authorities implemented an 11% price hike, which fell short of farmers’ expectations.

Ivorian farmers sought a 44% increase in the farmgate price after the market surge, aiming to enhance investments. In Ghana, authorities made a politically motivated decision to increase farmers’ pay by 64% in September 2023 to combat bean smuggling to neighbouring countries and gain political favour as elections approached in less than ten months.

However, this decision has led to significant repercussions as Ghana now faces the risk of losing access to a crucial funding facility due to a crisis in its cocoa crop, which has resulted in insufficient beans to secure the funds. The funding challenges in Ghana coincide with a bleak outlook for the cocoa harvest in 2023/24 estimated at 422,500 to 425,000 tons, half of the country’s initial forecast. Consequently, Ghana is seeking assistance from traders to bridge the funding gap, Bank of Ghana Governor Ernest Addison said. The Ghana Cocoa Board, responsible for regulating the industry, heavily relies on foreign financing to compensate cocoa farmers for their produce. Despite the surprise of a 64% price hike, farmers still feel they deserve better treatment, especially as the country grapples with an ongoing economic crisis escalating the cost of living significantly.

After weeks of global price hikes, Ghana takes the same path as Côte d’Ivoire in raising the price it pays farmers for their output after cocoa futures skyrocketed. The second-largest producer of the chocolate component boosted the farmgate price for cocoa beans by 58% to 33,120 cedis ($2,481) per ton for the remainder of the 2023-24 season, according to a statement from the Ghana Cocoa Board. COCOBOD has disclosed that this new price corresponds to 2,070 cedis for each 64-kilogram bag.

This is the second time the West African country has upped farmergate prices this season. It comes after Côte d’Ivoire raised prices by 50% to 1,500 CFA francs ($2.48) per kilogram for its mid-crop, the smaller of two yearly harvests that began this month and will finish on September 30. Higher farmgate prices should help alleviate the worldwide cocoa shortfall, as producers will have greater motivation to send over beans for processing and export.

There have been concerns that some workers are delaying delivery to earn more money. The rise may also encourage investment in farms with aged trees susceptible to disease. Still, payments remain much lower than those on the global market, and breaking the cycle of poor farmer recompense in West Africa requires more.

The COCOBOD wields significant control over Ghana’s cocoa industry, acting as a mediator between local farmers and global buyers by setting fixed prices for cocoa beans. However, this centralised control inhibits foreign investment, constraining profit margins and flexibility for international corporations.

Consequently, it hampers the sector’s competitiveness, hindering its evolution into a robust powerhouse and making it vulnerable to the encroachment of illegal miners. While government intervention offers stability and protects farmers from market fluctuations, over-reliance on such measures has prevented industry players from mastering market dynamics independently. This prolonged dependency has stunted the growth of Ghanaian cocoa farming companies.

Conclusion

Due to the high global demand for cocoa beans, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire must navigate this geopolitical landscape carefully as they supply approximately 60% of the world’s cocoa beans. Addressing the prevalent challenges involves prioritising measures to increase cocoa output, which has declined significantly.

It is crucial that the government ensures farmers receive fair prices for their produce, as their livelihoods are at stake. Not doing so could result in neighbouring countries taking advantage of the unmet demand, potentially redirecting crucial export earnings away. In the medium to long term, it is worrying that farmers in Ghana are looking to move away from farming cocoa because of decreasing government support. Nigeria went through this same process in the 1960s, and this brought down that country’s production.

A significant drop in Ghana’s production, combined with a lack of new plantations coming up in the Ivory Coast, will lead to a shortage of cocoa beans around the world and a surge in the price of chocolate. Given the current high global cocoa prices driven by shortages on paper, other West African countries stand to benefit from increased production. A more open market approach can enable cocoa-producing companies to expand regionally and internationally, akin to how South African corporations have leveraged their resources and expertise in telecoms and media across Africa.

Ghanaian and Ivorian cocoa farmers may explore countries like Nigeria, Cameroon, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Gabon and Togo, which offer favourable conditions for cocoa cultivation. Expanding operations into these countries allows cocoa farmers to solidify their position as leaders in the cocoa industry. However, political and security risks remain the elephant in the room for the region. Cocoa-producing countries must strike a delicate balance between meeting global demand, protecting the interests of local farmers, ensuring security for said farmers, and ensuring the industry’s long-term sustainability. Only through collaborative efforts and proactive measures can the chocolate industry emerge stronger from the current crisis and continue to serve consumers worldwide.